Historical Note: The primary source of information about Maj-Gen Worthington, especially his early days – is the book “Worthy” written by his wife Clara “Larry” Worthington published in 1961. There is also an unpublished manuscript that he wrote for his grandchildren. It must be noted that Worthington himself never read his biography, so there are some inaccuracies; mostly minor – that appears due to the 60 plus years between that day and the memory of it.

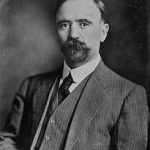

Many will recognize Major General “Worthy” Worthington as the father of the Royal Canadian Armoured Corps but not all will be familiar with his amazing life.

CB MC, MM, CD

The awards after Worthington's name are (Dates are when published in the London Gazette.):

CB - Companion to the Order of the Bath: The Order of the Bath is a British order conferred as a reward for exemplary military or civilian service. It was create in 1725 by George.

Worthington was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath on 5 June 1943 announced on the 1943 New Year's Honours list.

MM - Military Medal: Initiated 25 March 1916. Awarded to non-commissioned members (not officers) for "acts of gallantry and devotion to duty under fire". The award was discontinued in 1993 when it was replaced by the Military Cross.

Worthington was awarded his Military Medal on 12 March 1917 for actions on 7 January 1917 (Holds off a German raiding party with his machine gun) and the Bar on 9 July 1917 (For actions on 9-11 April 1917 at the Battle of Arras (Battle of the Scarpe)).

MC - Military Cross: The award was created on 28 December 1914 for "an act or acts of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy on land" for Officers (All ranks after 1993)

Worthington was awarded the Military Cross on 1 February 1919 for actions on 2 September 1918 near Villers France ( conspicuous gallantry leading his battery in open combat) and the Bar on 2 April 1919.

CD - Canadian Forces Decoration: Initiated on 01 September 1951. Awarded for twelve years service with good conduct.

Worthington was awarded both his CD and his Bar on 2 Oct 1950.

Frederick Frank Worthington was born in Peterhead, Scotland in the fall of 1889 to Henry and Kathleen Worthington. When he was young, the family emigrated to Los Angeles, California where Henry was a successful surgeon. Around 1900, both of his parents died and he moved to Nacozari, Sonora, Mexico to live with his half brother who worked the copper mines there as a mining engineer. Worthington worked at the mines as a water boy until his half brother died in 1902.

According to his autobiography, the mine had been raided by Pancho Villa and during that raid – his brother was killed. (This may be inaccurate. In 1902, Pancho Villa was captured in Durango state which is two states over from Sonora.) This left Worthington alone at the age of 12. For the next two years, Worthington lived with a man called Grindell who claimed to have studied at Oxford. Grindell had a love of books which was passed down to Worthington. For the rest of his life, Worthington was a ravenous reader and always had a book nearby. Their relationship came to an end when Grindell went in search of gold on Tiburon and failed to return.

At the age of 14, he went to sea as a Cabin Boy throughout the Southern Pacific reaching as far as Samoa and Hawaii. He served on various ships until he turned 16 and became an ordinary seaman after that. He visited Vancouver in early April of 1906. This was followed by his visit to San Francisco – just in time to witness the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906.

In 1907, Worthington shipped out on the steamer “San Juan”. It sailed from California to Mexico and on to Nicaragua. At Corinto (northwest Pacific side of Nicaragua), Worthington noticed a small gunboat having its engines installed. Worthington left the “San Juan” and joined the gunboat crew. It was here where he got his first taste of firepower. He noticed a group of soldiers attempting to get a Gatling gun to work. He approached them and within hours had the gun working. The supervising officer then removed Worthington from the gunboat and made him an officer with a Gatling Gun and 15 Nicaraguan soldiers that he was expected to train. (He notes this on his CEF Attestation Form)

After initial success, the war turned and Worthington along with five other mercenary soldiers escaped to Panama.

After a number of adventures, he found himself in Hermosilla, Mexico and in early 1908; he decided to visit his Uncle in Scotland. He crossed into the USA at El Paso and made his way as a train guard to Galveston and then as a ship’s waiter to New York (he was no good as a waiter, apparently threatening to dump a tureen of soup on a rude customer). After being robbed of all of his money, he postponed going to Scotland and went back to sea.

He decided to turn his hand to gun-running but was arrested and thrown into jail as soon as he stepped off of the boat in Cuba. The British Consul arranged to have him released and he returned to New York.

Worthington served as a junior engineer on several ships (mostly bad) until 1911 when he heard of the Revolution in Mexico led by the reformist Francisco Madero – and was off to join. By May, Madero had won and become President of Mexico, leading in democratic reforms and Worthington was off to sea again – to survey the waters of Patagonia.

In 1913, there was trouble again in Mexico; Madero had been assassinated and the generals began fighting for power. Worthington went to Mexico again as a guerilla and was wounded in the lower leg. After healing, he left Mexico.

By now, Worthington was a certified 2nd Engineer and planning on becoming a 1st. He was rushed ashore on 4 August 1914 due to a ruptured appendix, the same day that Britain declared war on Germany. After recovery, he decided to join the British Forces and shipped out on a tramp steamer where a German stoker attempted to drop a steel plate on him; the plate missed him but almost severed his little finger. He was unable to straighten that finger for the rest of his life.

He convalesced in California and when recovered, went to join the British Royal Navy in early 1915. He made his way to New York but was convinced to take passage from Canada rather than New York. Along the way, he also decided to join the Scottish Black Watch rather than the Navy.

In March 1916, he was in Bonaventure Station in Montreal where he joined the Canadian Black Watch (73rd Battalion CEF). After three weeks, Worthington sailed with the Battalion for England on 31 March 1916 aboard the “Adriatic”.

In March 1916, he was in Bonaventure Station in Montreal where he joined the Canadian Black Watch (73rd Battalion CEF). After three weeks, Worthington sailed with the Battalion for England on 31 March 1916 aboard the “Adriatic”.

Nacozari, Sonoma, Mexico

Nacozari (now known as Nacozari de García) is a small town in the northeast part of Sonoma.

The town sits high in the Sierra Madre Mountains.

Copper was discovered there around 1660 by Jesuit Missionaries and became a part of the Royal Mines Network. The mines were acquired by an American mining company in 1867, which was then sold to Moctezuma Copper Co, a subsidiary of Phelps Dodge. By 1907, the town had a population of 5,000.

Worthington was awarded both his CD and his Bar on 2 Oct 1950.

San Francisco Earth Quake, 18 April 1906

A massive earthquake (estimated 7.9 on the Richter scale) struck San Francisco in the early morning of Wednesday 18 April 1906.

80% of the city was destroyed and over 3,000 were killed. It is estimated that 300,000 people were homeless (the population was 410,000). The refugee camps lasted for over 2 years. Cost was estimated at the time to be $350 million ($8 billion USD in today's money)

Fires lasted for several days and over 4,000 federal army troops cleared ruble, patrolled streets to stop looters, and guarded building such as the US Mint.

Nicaragua-Honduras War 20 Feb–15 Apr 1907

Nicaragua’s dictator José Santos Zelaya invaded Honduras in support of Honduran insurgents, destroying a combined Honduran-Salvadoran army with machine guns (the first usage of those of those weapons in Central America). The Nicaraguans soon entered Tegucigalpa, prompting Honduran President Manuel Bonilla to flee to the Pacific port of Amapala, where he gained refuge aboard the USS Chicago. The United States intervened to arrange a final peace settlement, pushing Zelaya to accept a compromise regime under General Miguel Dávila.

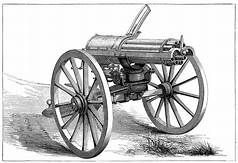

Gatling Gun

The Gatling Gun was invented in 1861 by Richard Gatling. It is a early machine gun.

The Gatling Gun was invented in 1861 by Richard Gatling. It is a early machine gun.

The gun system was mounted on a carriage and used six rotating barrels turned by a hand crank, and firing loose metal cartridges from a hopper.

It allowed unskilled operators to achieve a relatively high rate of fire of 200 rounds per minute.

The Gatling gun was used by Canadian troops during the North West Rebellion.

Mexican Revolution 1910-1920

By 1910, General Jose De La Cruz Porfiro Diaz had been President of Mexico from 1877 to 1910 (with a break for 4 years 1880 to 1884). Although seemingly a liberal, his enticement of foreign investors and the Mexican elite made Mexico prosperous at the expense of the poor and indigenous.

In 1910, Francisco Madero, a wealthy landowner; challenged Diaz in an election for the Presidency.

Diaz won the election (although the results were suspicious) but Maderno started an Armed Revolt in Northern Mexico. Maderno had support from the middle class, the farmers, and the labour unions.

On 21 May 1911, a peace treaty (Treaty of Ciudad Juarez) was signed between the two and Diaz resigned and headed into exile in France. Maderno was elected President by over 90% if the vote in November of 1911.

Although he had lofty demographic ideals, Madero's administration soon encountered opposition from both revolutionaries and conservatives. He governed as a moderate and did not move quickly on land reforms. Unions did not feel he was doing enough and foreign governments and companies thought that Madero was unable to maintain political stability

In 1913, the military took control of Mexico in a US-supported Coup and Maderno was arrested and later assassinated.

Mexican Revolution 1910-1920

In 1913, the military took control of Mexico in a US-supported coup d'etat and Maderno was arrested and later assassinated. The coup was led by General V. Huerta.

In death, Maderno became a rallying force for the differing parts of Mexico that opposed Huerta. Huerta was essentially a dictator and was supported by foreign and domestic large business, the wealthy land owners, and the Catholic Church.

Within a month of the coup, rebellion spread through Mexico. In the north part of the country, the "Constitutionalist Army" lead by the governor of Coahuila; V. Carranza including many of Maderno's fighters. Emilian Zapata led the Liberation Army of the South based in Morelos Province. Pancho Villa also led anti-Huerta forces.

In late October 1913, Huerta dismissed the congress and arrested those deemed hostile to him. Huerta also increased the size of the army from 50,000 when he took power to over 250,000 by early 1914. This growth was fueled by forced conscription.

Huerta could not stop the revolutionaries and by July 1914, he fled Mexico to Jamaica (then UK and Spain). He attempted to re-enter Mexico through the United States in April 1915 but was captured by US authorities and imprisoned in Ft Bliss where he died on 13 January 1916.

Following his defeat, all out civil war took place in Mexico with Carranza taking power in 1915.

Worthington and the 73rd Battalion arrived in Liverpool on 9 April 1916, with a strength of 36 officers and 1033 other ranks. After a few weeks of leave, training started in earnest at Sandling, Kent. Later that year they moved to Bramshott Camp in Hampshire. In his biography, an event takes place that demonstrates Worthington’s mindset foreshadowing his building of the Armoured Corps. Various small units were expected to attack machine gun positions (simulated by drummers). Acting Lance Corporal Worthington’s unit was the only successful unit. Rather than a frontal assault, Worthington (no doubt drawing on his guerilla experience in Mexico), stalked the drummer and snuck up from behind making the capture. Worthington was berated by a staff officer, stating “No British Soldier crawls into battle on his belly! There’s only one way to go after an enemy post. Stand up and march briskly forward!”.

March 1916 saw the 73rd move to France first as a brigade reserve and then to relieve the Royal Welsh Fusiliers at Kimmel, Belgium in September.

In October, Worthington picked up a Lewis gun on the battlefield which he reworked at a army workshop during a rest rotation. It should be noted that Lewis guns were manufactured in both the US and England. The American version had an extra spring which was missing on the English gun – but made the gun more reliable – when the unit returned to the front, Worthington’s English-made gun had the extra spring. Another modification that he made was to increase the speed of changing a broken return spring (a common problem). Changing the return spring normally took a minute but with his modification, it could be made in 10 seconds. However, during a Brigade machine gun competition, Worthington’s team’s 10 second change was noticed – but not commended. Worthington was arrested and charged with “Willfully damaging His Majesty’s property” by the supervising Captain. At the court of inquiry, his CO got involved and the charges were dropped. In a couple of months, all Lewis guns were modified with his innovation. (Later in 1925, he was at the British Military College of Science where he was informed that the modification to the gun was invented by a Canadian. He then found out that the officer who arrested him submitted his innovation and claimed the credit.)

Worthington says he was a witness to the first use of British Mark I tanks at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette (part of the Battle of the Somme ) on 15 September 1916. (Note: According to the War Diaries of the 73rd Battalion, the unit was in Kimmel which is over 110 km from Flers-Courcelette; his unit was present when tanks were used at Arras). Of the three tanks that he could see; two broke down but the survivor was able to break the German line. By this time, Worthington had been promoted to Corporal and commanded a Lewis gun section.

Around Christmas 1916, the Battalion marched for six days to Villiers Aux Bois to support the the Arras sector (area around Vimy Ridge). The unit participated in both small and medium trench raids on the Germans during this time. On 7 January 1917 (Note: the biography states that the date was 6 January but the 73rd’s War Diary confirms the action on the 7th and mentions Worthington by name), Worthington was awarded the Military Medal for his conduct in one of these raids, holding off a German counter attack with his machine gun. From a shell hole, he was alone until joined by a member of the 44th Battalion named Quigley. That story concluded with Worthington visiting the 44th and finding that Quigley was disciplined for being away from his post and later was killed. (Note: The nominal roll of the 44th does not include any member named Quigley, nor do the records of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission or the Canadian Book of Remembrance include a soldier named Quigley – perhaps it was a nickname.) Constant casualties weakened the Battalion until their status of sustainable was in question as early as February 1917.

On a raid in early March, Worthington took part in a large raid that failed when the wind changed and their support gas blew back on the attacking troops. As the Germans prepared to counter attack, Worthington (alone with his gun) along with the survivors of the attack dashed back to the lines. While traversing no-man’s land, Worthington and another soldier came across a wounded and blinded officer. Finding a flask in the officer’s pocket, they gave him a healthy “medicinal” tot and then each of the two had one for themselves. Worthington put the flask in his haversack and they evacuated the wounded officer. Worthington carried the flask until 1921 when he met the officer in Montreal and returned it.

It was at the Battle of Arras where Worthington was wounded. Initially, on the first day; he is wounded by a shell burst taking splinters in his neck and arm – these wounds are superficial and he continues in the lines. By 11 April 1917, the battalion is in drastic need of relief but no relief is forthcoming. Worthington is wounded again, but this time in the leg and is shipped to hospital where he stays for three weeks.

While he is in hospital, the 73rd Battalion is first dissolved (16 April 1917) and then disbanded (19 Apr 1917).

73rd Battalion (Royal Highlanders of CanadaCEF

The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders of Canada) has existed since 1862. During WW1, they raised three infantry battalions for overseas duty; the 13th, 42nd, and 73rd.

The 73rd Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada), CEF, was authorized on 10 July 1915 and initially commanded by Lt-Col Peers Davidson. They started recruiting in Montreal starting on 3 September 1915. Initial training was at Base Valcartier and they embarked for Great Britain on 31 March 1916.

The Battalion landed in England in April of 1916 with 36 officers and 1033 other ranks. After training in England, The Battalion was attached to 12th Canadian Infantry Brigade as a part of the 4th Canadian Division.

The 73rd landed in France on 13 August 1916 and served in Belgium near Ypres and then near Kemmel in September.

October found the Battalion in action at the Somme.

In December 1916, the Battalion moved to the Arras sector where it rotated in and out of the line until the attack at Vimy Ridge 4 April 1917. They attacked Hill 145 on the 4th and achieved all objectives. A Counter-Attack was beaten off on the 11th and was relieved on the 13th.

Due to the high level of causalities taken by the Battalion, the 73rd was broken up and most of the men transferred to the 13th or 43 battalions.

The 73rd Battalion was disbanded on 16 April 1917. It is perpetuated by the Black Watch of Canada. It was awarded the following battle honours: SOMME 1916. Ancre Heights. ANCRE 1916. ARRAS 1917. VIMY 1917. FRANCE and FLANDERS 1916-17

Lewis Gun

The Lewis Gun was a light machine gun that saw extensive service during WW1 but was used up to the end of the Korean War. It was used both by the infantry and as an aircraft gun.

The Lewis gun was invented in the United States in 1911 by Col Issac Lewis. It was not initially adopted by the US due to conflict between Lewis and Gen Crozier of the Ordnance Dept.

Lewis left the US and started a company in Belgium to manufacture Lewis Guns. The Birmingham Small Arms Company (BSA) bought a license to manufacture which made Col Lewis a wealthy man.

The Lewis gun is gas-operated. When the gun fires, some of the propellent gas is routed from the barrel and pushes against a piston which opens the bolt and cocks the gun.

The Lewis gun uses a pan shaped magazine holding either 47 or 97 rounds.

The Lewis gun was also manufactured by Savage Arms in the US.

Over 200,000 were built in both wars.

The Lewis gun fired .303 and .30-06 rounds. It could fire up to 600 rounds a minute and was effective to 800 m.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission was created by Royal Charter on 21 May 1917. Its duty is to maintain the graves and the cemeteries of the more than 1.7 million dead from Commonwealth countries from both world wars.

The Commission manages 23,000 locations in over 150 countries. Where there are no know graves, the Commission also builds monuments with the names of the fallen inscribed on them.

The CWGC maintains a website where visitors can find and research graves and cemeteries as well as learning about their good work. That website can be found here.

Canadian Book of Remembrance

On 1 July, 1917, Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden dedicated a space at the Houses of Parliament for a memorial to those lost their lives during the Great War. That turned into the Peace Tower.

The initial concept was to inscribe all of the names onto the sides of the tower. However, with more than 66,000 names - there was not enough room. So a "Book of Remembrance" was substituted instead.

The books are illuminated manuscripts with each name written upon calf skin vellum by a skilled calligrapher. The two world war books have the most illumination with a decorated top border and unit badges.

There are currently 8 Books of Remembrance held in the Peace Tower's Memorial Chamber:

The Books of Remembrances can be electronically searched here.

Battle of Arras 9 April 1917 - 17 May 1917

The Battle of Arras (also known as the Second Battle of Arras) was a British and Allies offensive in France from 9 April to 16 May 1917. Allied Forces attacked German defences near Arras in support of a larger French offensive (Chemin des Dames, hills of Champagne). The British achieved the longest advance since the beginning of the war. The advance soon slowed and the Germans counterattacked. The battlesoon stalemated and by the end of the battle, the British Third and First Army had suffered about 160,000 casualties and the German 6th Army about 125,000.

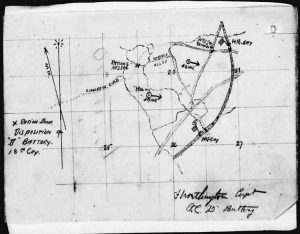

Worthington is in hospital for three weeks. After that, he spent some time guarding POWs but returned to headquarters to meet Lt-Col. H.C. Sparling. Sparling informed Worthington that he was being commissioned and that he is getting the Bar to his Military Medal. In July, Worthington attends an officer candidate course at Pribright, Surrey. Following that, he attends a British machine gun course and is then assigned as Commander ‘D’ Battery; 18th Machine Gun Company as of 15 March 1918 in Seaford, England. (Note: there are some date variations between the biography and the 18th MGC War diaries). A battery was considered 8 guns with crews of four or five.

On 28 March 1918, the 18th MGC joined the 5th Canadian Machine Gun Battalion under Brigadier-General Raymond Brutinel. Upon arriving, General Brutinel inspects the Battery and first puts Lt. Worthington in command due to him being the only officer to have seen combat (and his MM and bar). Second, he field promotes Worthington to Captain. (Note: the 18th CMG War Diaries have Worthington assigned as Officer Commanding as early as 15 March and promoted as of 3rd April along with the Lieutenant in charge of the other battery.)

Worthington’s battery went into the line on 8 April 1918.

On 8 June, 1918, 18th Machine Gun Company was disbanded and the troops absorbed by the 1st Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade. Worthington and “D” Battery, 18th C.M.G. Coy, became “E” Battery, 1st C.M.M.G. Bde. The Brigade went into action in and around Maison Blanche near Vimy Ridge. Training on firing while in motion was done from the back of trucks.

12 August sees E Battery moving to support the infantry who have taken the village of Vis-en-Artois. Worthington and two others take motorcycles to check the route to the village. After he drops his two riders behind him to carry messages, Worthington is surprised as he passes the outskirts of the village to find a pair of German sentries. Zipping past them on his motorcycle, he runs into a large party of German soldiers. He escapes into a street only to find it is a dead end. He abandons his motorcycle and hides in the basement of a nearby house. The Germans search but do not find him. Rather than leaving immediately, he goes to the top floor and finds a window where he can observe the German positions. Leaving the house, he encounters the lead elements of the Cameron Highlanders. He then takes them to the window and engages the German positions with their Lewis gun.

On 19 August 1918, Worthington assumes command of E battery. On the 21st, Worthington is permanently promoted to Captain. The group was a part of the Battle of Cambrai where Worthington is awarded the Military Cross for actions near Villers. The Independent Force’s role was to take and hold the Canal du Nord. By October, the brigade was back in the Corps Reserve. On 2 October 1918, the five batteries were loaned to the 2nd Canadian Division. On 21 October 1918, Worthington and E battery were tasked to take and hold a bridge over the Escaut Canal near the town of Valenciennes. Taking a round-about route, they come across an woman who speaks English. They are informed of a group of Germans eating breakfast, who are quickly captured along with maps. Worthington and his battery have penetrated far behind enemy lines and are only 4 or 5 miles from their objective. Driving at top speed, they capture the bridge and eliminate the German engineers readying the bridge for destruction. Worthington defends the bridge with two armoured cars, eight trucks, 12 machine guns and about 70 men. The Germans attempt to retake the bridge three times. They are relieved the next day and Worthington receives the bar to his MC. By this time, both E and C batteries were under the command of Worthington and the advance to Mons continued. It was on that advance when the order to cease fighting came on 11 November 1918.

However, Worthington had left to attend the machine gun course at Camiers on 10 November, so missed the event with his unit.

On 17 December 1918, Worthington takes command of B Battery but goes back to E battery by the 29th. On 5 January 1919, Worthington is awarded the Bar to his MC. Worthington and his batteries remain in Germany on Garrison duties until the April of 1919 when they return to England.

In England, Worthington is recruited by Colonel J. Boyle to raise a force to defend Romania from Austrian Bolsheviks. The Government of Canada steps in just before they are set to leave in July 1919 and are prevented from going.

18th Machine Gun Company

A Machine Gun Company, of the Canadian Machine Gun Corps, was attached to each Canadian Infantry Brigade, until the formation of Canadian MG Battalions.

The 18th C.M.G. Coy. was originally a Brigade Machine Gun Company of the 5th Canadian Division.

However, this Division was broken up in England, prior to active service.

On March 25th, 1918, the Brigade Machine Gun Companies of the, now non-existent, 5th Division, arrived in France. They were used to relieve experience units sub-section at a time.

Along with the 17th C.M.G Coy and 19th C.M.G Coy, it formed the 5th Canadian Machine Gun Battalion, yet was used as an independent unit.

In June, 1918, it was disbanded and the troops absorbed by the 1st Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade. “C” Battery, 18th C.M.G. Coy, became “D” Battery, 1st C.M.M.G. Bde, and “D” Battery, 18th C.M.G. Coy, became “E” Battery, 1st C.M.M.G. Bde.

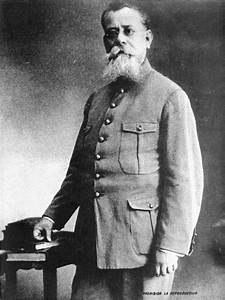

1st Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade

The roots of the 1st Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade takes place only a week after the declaration of war. On 11 September 1914, the Minister of Militia and Defense; Sam Hughes, approved the formation of the Automobile Machine Gun Brigade No. 1.

This was the first motorized armoured unit created by any country in the world.

The foundation of this unit was the first purpose built armoured vehicle which was the brain child of Raymond Brutinel (1882 - 1964). He was a Frenchman who served during WW1 for France and then emigrated to Canada where he made his fortune. He had proposed to the Government of developing a military unit using Machine Guns mounted on lightly armoured vehicles.

To build these vehicles, he sourced Colt Machine Guns, Chassis from Autocar of New York, and steel plate from Bethlehem Steel. By September, the unit was kitted out with 20 vehicles (8 Light Armoured cars each with two Machine Guns, 5 supply trucks, 4 staff cars, a gas truck, a repair truck and an ambulance). The unit manning was 1 major, 3 captains, 5 subalterns, 4 sergeants,

2 sergeant artificers, 4 corporals, and 101

privates. This was also known as the Sifton Brigade.

The unit made it to France by 16 June 1915, where its name was changed to 1st Canadian Motor Machine

Gun Brigade (1st CMMGB).

By this time in the war, the trenches were in place and the opportunity for mobile operations was limited. Brutinel focused on training and developing new and innovative tactics such as the use of indirect fire, using machine guns in the offense, and employing concentration of fire. These innovations were soon copied by other armies and Brutinel was appointed the Commanding Officer of the Machine Gun Corps in 1916.

By June 1916, three more batteries joined: "C" (Borden), "D" (Eaton), and "E" (Yukon). These batteries carried their guns on Napier Light trucks and did not have armoured cars.

To understand the power of this mobile force, the Brigade was highly mobile, with 300 men and the ability to concentrate the fire of 40 heavy machine guns. A typical Division of 10,000 would have 64 machine guns and not mobile.

The Brigade was utilized at Vimy Ridge in April 1917, The 5 batteries moved in a leap frog fashion with the static batteries providing covering fire to the moving units. In this fashion, they were able to move over 5 kilometers.

In 1918, the German Army made a large offensive attack aimed at Paris. The Brigade was assigned to the British 5th Army for support in their retreat. By this time, the Brigade had grown to the five batteries but also 20 trucks and 65 motorcycles. The Brigade acted as a flying unit, moving from place to place stiffening the defense with their firepower. In the next two week, they lost 2 armoured cars, 37 killed, 116 wounded, and 11 missing - 40% causalities.

In March 1918, the 5th Canadian Division was disbanded in England. This set up Brutinel to restructure the Machine Gun Corps by adding a second Motor Machine Gun Brigade. the 2nd Canadian Machine Gun Brigade was formed by taking two batteries from the 1st as its corps. The 3 Machine Gun Companies from the 5th Canadian Division are then split between the two Brigades.

During the Allied Counter Attack ((Amiens, 8 August 1918); Brutinel commands the Canadian Independent Force consisting of both Motor Machine Gun Brigades, a Trench Motor section, 60 motorcycles, and 300 infantry cyclists. The 1st Motor Machine Gun Brigade had two armoured car batteries and three truck machine gun batteries. The 2nd had one armoured and four truck batteries.

Although the units maintained a level of success, their ability to rapidly move became affected by craters, destroyed bridges, and road blockades. To assist this, in October 1918, two squadrons of the Canadian Light Horse (Cavalry) are attached to the group – too late in the war to have any real effect.

Worthington returned to Canada with his unit in late spring of 1919. He is offered a position in the Permanent Forces and chooses to accept it. His first tasking is to re-organize the two Montreal Reserve Machine Gun units. After that, on 1 January 1920, he is promoted Acting Major in the Canadian Machine Gun Corps.

In 1922, the Machine Gun Corps was disbanded. The decision was to disband the Machine Gun Battalions and place a machine gun company in each of the three permanent Infantry Units. In December of 1922, Worthington was courting Clara and proposed days before he shipped out to Winnipeg to become a member of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI).

Major Worthington is taken on strength with the PPCLI at Fort Osborne Barracks in Winnipeg Manitoba. At the time it was the home base for the PPCLI but other units such as a squadron of the Lord Strathcona’s Horse, an RCAF detachment, a battery of artillery, and the usual support detachments. Worthington participated in training and summer camp but in 1923 and 1924, his focus was on preparing for his Captain’s exams. Since his promotion was a field promotion he had to pass his Captain’s exam – in order to be allowed to pass his Major’s in order to keep his rank. Noting that he had no formal education, this was a significant challenge. He wrote his exam in the last week of October 1924 and then took leave to Toronto to get married. Then in January 1925, he and his new wife, set sail as he was posted to the English Machine Gun School in Netheravon, Wiltshire. Worthington spent over 5 months at Netheravon, both as a candidate and after that as an instructor. He also spent 6 weeks at the Woolwich Arsenal. He and Larry were back in Winnipeg by Christmas 1925.

In 1927, Peter John Vickers Worthington was born – “Vickers” after the machine gun. Two years later a sister Robin joined the family.

1930 saw the Canadian Government flirt with mechanization. Twelve Carden-Loyd Carriers were purchased and Worthington, knowing the power of mobility, was on the first (eight month) course in London, Ontario in January 1931. The Instructor from Vickers did not show so Worthington nominated himself Chief Instructor and gave the course. He passed.

Back in Winnipeg, Worthington worked with the University of Manitoba to research the use of the Carden-Loyd carriers in very cold weather. In 1934, he was posted to Toronto as Deputy Assistant Adjutant & Quarter Master General. In June the next year, he was in Ottawa to run Prime Minister Bennett and the Canadian Government’s Unemployed Relief Camps. These were Depression era camps set up all over Canada to supply some level of employment to the unemployed.

Canadian Machine Gun Corps

There are two iterations of the Canadian Machine Gun Corps. The first is created during the Great War and the second after it.

There are two iterations of the Canadian Machine Gun Corps. The first is created during the Great War and the second after it.

The first is created on 16 April 1917 and is intended to bring all of the Machine Gun units under a single command structure. It initially consists of:

By the end of the war, the Corps contained:

In total, 655 Officers, 12,750 other ranks with 488 machine guns.

After the war, the Corps was reformed on 1 Jun 1919 as an administration formation. It was a part of the Militia and consisted of:

On 3 November 1919, the Canadian Machine Gun Brigade was created as part of the Permanent Forces. In 1921, the "Royal" Prefix was added to the "Royal Canadian Permanent Machine Gun Brigade."

In 1924, the Royal Canadian Permanent Machine Gun Brigade was disbanded and its members sent to the three Permanent infantry Battalions to set up local machine gun units.

In 1936, the Machine Gun Corps was disbanded but the number of Machine Gun units increased from 12 to 26 battalions.

Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry

The Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI, "Pats", or "Patricia's") is one of three Canadian Regular Force Infantry Regiments.

The Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI, "Pats", or "Patricia's") is one of three Canadian Regular Force Infantry Regiments.

The unit was formed for WW1 by Capt. A. H. Gault in Ottawa Ontario. The Governor-General at the time was the Duke of Connaught and he was approached for permission to name the new unit after his daughter Princess Patricia of Connaught.

The unit was approved on 11 August 1914, and recruiting began. By 19 August, 1,098 had enlisted with less than 50 not have served previously.

The unit arrived in England 18 October 1914 and were in France by Christmas.

The Patricia's have served as a regular force unit of three battalions and have been in every Canadian Conflict since inception.

When the Relief Camps were closed in 1936, Worthington was chosen to run the first Armoured Vehicle School in London, Ontario. As the school started up, Worthington was breveted to Major having been a captain for nineteen years. He was also required to attend the Royal Tank Corps school at Bovington. The remaining five officers and eighteen other ranks were trained in engines and maintenance at RCAF Base Trenton.

Worthington also trained at the Mechanical Engineering War Establishment and the Gas School. He then did a turn as an instructor at the Tank School before returning to Canada in April 1938 and going directly to Camp Borden.

The Canadian Armoured Fighting Vehicle School (CAFVS) had little equipment and due to the depression – could not count on getting much. They had the twelve Carden-Loyd carriers purchased in 1931/2 and to improvise or “tactically acquire” engines, tools, and everything else needed for training.

In August of 1938, as commandant of the CAFVS, Worthington became an Acting LCol which made him “Captain Brevet Major Acting Lieutenant Colonel Worthington MC MM”.

In September of 1938, the first new vehicles arrived at the CAFVS – a “Dragon” (tracked artillery Tractor) and two Vickers Light Tanks. It would not be until August of 1939 when another 14 Lights would be be delivered.

Training was always difficult although the cadre of the CAFVS went above and beyond to train the new six armoured units as much as possible. Spare parts were always in short supply and many had to be made on site. Worthington was also preaching armoured doctrine to whomever would listen.

With the declaration of war, Ottawa mobilized the Ontario Regiment and the Three Rivers Regiment. They also renamed the CAFVS to Canadian Armoured Fighting School Training Centre. Then they did nothing else.

Worthington continued to press the need for tanks and armoured vehicles for modern mobile and combined arms warfare. He was also continually turned down. In January 1940, Worthington is told to shut down the CAFVTC and convert to training infantry drivers. He received 20 Dodge Fargo trucks (forerunner of the WC series) and began training drivers. He also included the wireless, tactics and gunnery components – just forgetting to inform Ottawa. He was given 400 new recruits to train but no officers or NCOs. Working with psychologists from the University of Toronto, he introduced the use of an Aptitude test to select 50 men for promotion to NCO. Of these 45 were shown to become excellent leaders and were promoted rapidly. This was the first use in the Canadian Military to use testing for selection.

In late April of 1940, Worthington was speaking at the Military Institute in Toronto and was asked a question “How will tanks make it through the Maginot Line?” Worthington replied ‘They won’t. They’ll go around them.” and then drawing the flanking maneuver through Belgium and the Netherlands on a nearby map. A photographer from the newspaper took a picture of it and it made it onto the front page the next day – “Worthington on the German Attack”. Of course, this landed him in front of the General in charge of Military District 2 with the threat of a severe reprimand – which would end his career. Fortunately for him, the German army attacked through the lowlands as Worthington had predicted. The matter was dropped.

On 27 May 1940, both the Toronto Star and the Toronto Telegram ran stories critical of the government due to the lack of Armour in the army. Two weeks later, Worthington was contacted by the Minister of Defense, N.M. Rogers for a meeting in Toronto on 10 May. Rogers died in a plane crash flying to Toronto for the meeting. His replacement J. L. Ralston ordered Worthington to resubmit a paper that he had written detailing the structure of the armoured corps. This paper was accepted and Worthington was then asked to write the order for the creation of the Armoured Corps and the conversion of Cavalry Regiments to Armour. The order was published 13 August 1940 and at the same time, Worthington was promoted to full Colonel. He was now Commandant of the CAFVTC, Administrative Officer of the Canadian Armoured Corps, Technical Advisor to the Tank Board in Ottawa, and Commander of the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade.

Worthington was instrumental in the design and development of the Ram tank but wanted a larger gun.

In September of 1940, Worthington arranged for the purchase of 265 M1917 tanks from the Rock Island Arsenal in Illinois. They had been built in 1917 but had never been used. They were going to be sold to scrap dealers for $16 a ton but Worthington arranged the purchase and delivery for $20 a ton. Rock Island also threw in 45 tons of spare parts and 13 engines. As the US considered themselves neutral, they could not sell arms to Canada. So the manifest stated that they were selling “Scrap Iron” to the “Borden Iron Foundry” in care of “Mr. Worthington”. The tanks crossed the border without incident.

The 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade became the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade and the new 5th Canadian Division became the 5th Canadian Armoured Division. The patch for the 1CATB was a Ram – taken from the gold ring that Worthington wore which featured a goat (which he called a Ram). This is also where the name of the first Canadian tank (Ram) is derived from.

In Sept of 1940, General (then Colonel) Worthington made a visit to Fort Knox, Kentucky. He was the guest of the 7th Calvary Brigade of the 1st US Armoured Corps that was under command of Brig Gen Adna Chaffee Jr. (namesake of the later M24 Chaffee tank). The US at the time was not engaged in WW2 but a mutual defence agreement between the US and Canada had been signed two weeks prior to the visit. The pictures below are part of a scrapbook created at the time. The Scrapbook is Archive ID RCAC356.

In April of 1941, Worthington went to England and in June – 1CATB left Canada to join him. The Brigade settled in West Lavington Downs (Salsbury plains) under General Harold Alexander but in October moved to Hindhead under command of General McNaughton.

Before the year was up, McNaughton had informed Worthington that he was to command the 4th Canadian Armoured Division and promoted him to Major General. Worthington took command of the Division at Camp Debert, Nova Scotia on 28 March 1942.

The summer of 1942 was nothing but intensive training for the 4CAD. There were only two trained tank drivers on hand; Maj-Gen Worthington and Col Gaisford. So they had to drive all of the 165 Ram Tanks off of the flatcars. Training was set up using mass production techniques. Worthington and Gaisford would get up at 4am and each train three soldiers on simple driving: starting, changing gears, and driving. The next day, they repeated with the same six men. On the third day, each of those six got three candidates to train. Of the 18 trained in the next set, 9 were selected for advanced driver training by the General and the Colonel. Over a short period of time, the number of men trained was enormous. Training started at 4am every day and proceeded in shifts until midnight. Similar programs were set up for gunnery, wireless, and tactics. Against all odds, the Division was ready. In June, selected personnel were already in England for specialized training. By late August, the Division was heading overseas.

Worthington landed in England on 21 August 1942. Upon landing, he heard the news of the disaster at Dieppe.

When 4CAD arrived in England, training was to commence but the supply of tanks was limited. There were modifications required to the Ram Tanks before they could be released. When Worthington visited the Jack Olding Company where the work was to be done, there were scores of Rams waiting to be upgraded but not enough mechanics. Worthington worked out a deal with the owner: Worthington would supply working parties and drivers but his division had to get every second tank. Unhappily for the 5CAD; the drivers from the 4CAD would often get “lost” and end up delivering the tanks to 4CAD anyway. 5CAD complained and Maj-Gen Turner called Worthington for a mild rebuke – mild because the delivery quotas had all been met ahead of time.

By March 1943, the 4CAD was trained up to the point where they could similar sized British units. In November 1943, 4CAD participated in exercise “Bridoon” against the 9th British Armoured Division. 4CAD started by “losing” a set of fake operational plans where the British could find them. When the British took the bait, the Canadians were able to knock out half of the British Armour and capture one entire Armoured Regiment. 4CAD prevailed on the next two days as well using guile and subterfuge. The 9th complained that the Canadians did not fight fair.

By the end of the year, General McNaughton was pressured into giving up his command. Days later, Worthington was informed that he was also to return to Canada for other duties. His age and health were given as reasons.

By April 1944, Worthington had returned to Camp Borden as Camp Commandant. The camp had grown to hold over 25,000 including training centres for Armour, Infantry, Provost, Medical, Service Corps among others. Morale was low. There was poor discipline with a high incidence of absent without leave, theft, and petty crime. Theft of gas was commonplace – Worthington ordered that the military gas be dyed and anyone caught with dyed gasoline would be charged. The military policed checked every car entering or exiting the base. Many officers and men were caught. Similarly, theft and illegal use of military vehicles were stopped through searching of all vehicles and the use of land mines on the back trails out of the base. The mine’s triggers were set 50 yards away from the mine so that no real damage was done but the point was made.

There were several times when Worthington showed that he was a soldier’s soldier. In June of 1940, the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA) was passed. This act allowed for conscription for service but only for defense of Canada. Going overseas was still voluntary. Those conscripted under the Act were referred to as Zombies, given unsuitable uniforms and were not allowed badges. They were used as labour around camps and not as soldiers. Worthington did not approve and ordered that they be properly equipped and treated as the other soldiers. The word Zombie was banned. In the same vein, those as young as 17 could join the army but could not go overseas until the age of 19. Many young men joined for the adventure or to serve their country but found themselves relegated to menial jobs. Worthington set up a special unit just for them and moved the unit to Meaford. Rations especially milk were increased and they were trained so well that they became demonstration troops for teaching battle drill to the older but new recruits. Their loyalty was so high that when one young lad was hit ( ear lobe, boot heel, arm grazed) by a machine gun during a live fire exercise; he went AWOL from the hospital to return to Meaford as he did not want to miss any of the exercises.

In August of 1944, Peter J. Worthington joined the Navy. He commented that one Worthington in the Army was enough. (Although it should be noted that he did serve in Korea with the PPCLI as a junior officer.)

In March of 1945, Worthington was appointed as Commander in Chief, Pacific Command. Not only did he command all of the regular forces – he also set up an auxiliary corps; the Pacific Coast Militia Rangers. The Rangers grew to 115 companies and over 14,000 members. The Pacific Coast Militia Rangers were stood down after the war but in 1947, the Canadian Rangers was created using the same model. In 1949, Worthington was named Honorary Colonel Commandant of the Canadian Rangers.

After Japan surrendered, Worthington became General in Command of the Western Region and moved back to Edmonton.

On 29 September 1949, a combined air/ground exercise took place at Camp Wainwright Alberta. The exercise was code named “Adios”. As part of the exercise, Worthington commanded that lead tank in the final assault. The next day, he handed his command over to Maj-Gen Penhale and retired. He was 58 and had spent thirty-two years in uniform.

Retirement did not sit well for Worthington. In 1948, he was named Civil Defence Coordinator for Canada. In 1951, the Civil Defence unit was transferred from Ministry of Defence to the that of Health and Welfare.

In 1949, he became Honorary Colonel Commandant of the Royal Canadian Armoured Corps.

In 1957, his appointment as Civil Defence Coordinator was not renewed. That same year on his birthday (17 September), he retired having grown Canadian Civil Defence to over 200,000 people.

On 8 December 1967, Maj-Gen F. F. “Worthy” Worthington, father of the Royal Canadian Armoured Corps; died at Ottawa’s Military Hospital. His wife Clara (“Larry”) wrote in his biography; “When Worthy dies… he doesn’t want to go to heaven, he wants to go to Camp Borden” – of course such things are not allowed but that was never a impediment to Worthington. After a military funeral in Ottawa, an RCAF Caribou flew his remains to CFB Borden, and he was interred at Worthington Park. A troop of 4 Centurion Tanks fired a 13 gun salute in his honour and he was received by a 200-man guard of honour.

On 11 November 1992, Clara Worthington passed away and was interred next to her husband at Worthington Park by the RCAC.

By using this site, you agree to our terms and conditions.

Terms and Conditions.

Copyright

Contact us by email.

© 2020 Royal Canadian Armoured Corps Association